The Martindale Pioneer Cemetery

In a small rural community in Martindale, Quebec, a magnificent limestone Celtic cross stands guard over a burial ground where a number of survivors of Ireland’s Great Famine found a peaceful final resting place.

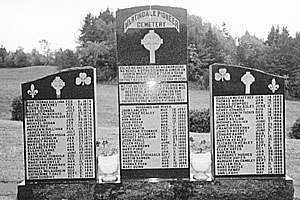

MARTINDALE Pioneer Cemetery, the burial site for survivors of the Irish Famine who settled in the Gatineau Valley.

THE CELTIC CROSS which stands in Martindale Pioneer Cemetery.

The cross is inscribed in Irish, English and French with these words: “May the light of heaven shine on the souls of the Gaels who left Ireland in the years of the Great Famine to find eternal rest in this soil. They will be remembered as long as love and music last.”

THE MONUMENT with the names of all those buried in Martindale Pioneer Cemetery.

Over the years many people have visited this cross and wondered how this memorial came to be on this site. The following is an outline of information which will form the basis for a book on the Martindale Pioneer Cemetery and the role of Catholine Butler [formerly known as Elaine McCay (née Gannon)] in this monument.

Catholine and Maura’s Story

Becoming The Celtic Connection

Catholine Butler and her daughter Maura McCay established The Celtic Connection newspaper in Vancouver, British Columbia in 1991. For almost 15 years, the monthly publication has served as information central for Celts throughout Western Canada and the U.S. Pacific Northwest. Each month over 30,000 readers, read The Celtic Connection.

It was a long journey from the Gatineau Valley in Quebec to Vancouver, B.C. for both women and one filled with both adventure and tragedies but one extraordinarily rich in experience. In other words: A typical story of The Irish in Canada.

Mothers and Children : A Bond Beyond the Grave

By MAURA McCAY

Catholine Butler was born as Elaine Gannon in 1934 and her ancestors came out from Ireland during the years of the Great Hunger [1845-1852] and settled in the area of Western Quebec known as the Gatineau Valley.

It was here, among her extended family in this rural community, that she was raised. Her parents Ambrose and Gladys Gannon had five children: Elaine [Catholine Butler], Michael, Myrna [Daly], Faye [McCambley], and Linda [McKale].

Many of the early settlers in this area were refugees who had overcome the poverty and the horrors of famine which was ravaging their homeland. They had survived the voyage across the Atlantic on the infamous overcrowded coffin ships on which thousands more perished. Cholera and various other diseases were rampant among these weakened people and many ports were closed to the Irish during this terrible period.

GLADYS and Ambrose Gannon. Catholine’s parents at the family farm in the mid-seventies.

These survivors arrived at Grosse Île in Quebec, the main port of entry during that period which acted as a quarantine station to ensure the sick and dying did not spread their illness. It was here again that thousands more Irish found their final resting place.

The settlers who arrived in the Gatineau Valley were no doubt traumatized people. The horrors they had lived through to arrive among these green hills would remain with them despite finally finding a tranquil place to build a peaceful life. Their hopes lay in the future of their children and their children’s children.

The families who settled in the area were awarded grants of land by the Quebec Government and established homesteads in villages and small enclaves with names like Low, Martindale, Venosta, Fieldville, Brennan’s Hill and Farrelton.

It was in the early 1960s that Catholine [whose married name was Mrs. Thomas (Elaine) McCay] became involved in a project to recognize these ancestors which would become a life-long undertaking. At that time she was a young mother of three small children and she was pregnant with her fourth child.

During this period she was very sick. After giving birth to a stillborn infant son, she became progressively weaker. She was frightened that soon she would also perish and she was deeply troubled about the fate of her three young children who needed their mother. It was in her connection with the ancestors that she found a solace which helped her survive the ordeal.

She began visiting the graveyard where her ancestors were buried and in her despair, she began to ask for their assistance. She made a promise that if she could survive her ordeal and see her children grow, she would put her strength into restoring this cemetery.

Catholine explained, “my ancestors were buried in that graveyard and it had fallen into disrepair. Nothing was being done about it and in fact it was going to be lost if no action was taken. Brush was piled on top of the stones. Cows were trampling through the burial grounds and headstones were being knocked down. Many people said ‘isn’t is a shame’, but nothing was done about the situation.”

There were a number of ornately carved headstones. Others were very simple, just a single white cross or a small white headstone. Some were carved with images of shamrocks and harps, but time had worn away many of the names and dates carved into the stone.

There was a significant number of young women who had died in childbirth and infants who had died at birth or shortly afterwards. This information resonated with Catholine as she says,“at the time, I thought I was also going to die, and in fact, I came very close to dying.

“After the child was stillborn, my health deteriorated further and I knew I was very sick. Often, I would go to the graveyard and sit on the logs that had fallen among the headstones. I would speak to my ancestors and the people buried there and ask for their help.

“I told them the situation with my young children and how sick I was and said if I could survive this and get better to see my children grow up, I would do everything in my power to get this graveyard fixed up. I would put their names up to ensure their history would not be lost. I called it a pact with the ancestors that I made at that time.”

For a long time the doctors were unable to diagnose Catholine’s illness and finally she became so ill and depleted that she received medical intervention to save her life. She underwent surgery for a hysterectomy and that was a major turning point for her. Afterwards, while still very weak, she began to recover and it took a year to fully regain her strength. She often said, “I was so sick for so long that when I finally got better, I put my running shoes on and I never looked back.”

As soon as she could, Catholine teemed up with Mrs. Johnny McSheffrey and they began to work together on the restoration of the graveyard. To begin, the two women went down to Farrelton Parish as that was where the parish records begin, since in the early days there was only a visiting priest at Martindale Parish.

Father Cauley was the priest in Farrelton in the 1960s, and he said, “yes, of course, the books are open for you to come down and take a look.” The priest was most welcoming and Catholine said, “Father Cauley was very good to us. He told us to take as much time as we needed. His mother, who was also his housekeeper, would make tea for us and bring it in while we were studying the records.”

When the women finished reviewing the books in Farrelton, they needed to proceed to Martindale Parish to continue the trail of their research. Catholine said, “I phoned Father O’Donnell, who was the priest at Martindale and he was not very happy about us coming in at all. He said the books belonged to the parish and he was concerned about what were going to do with the information and suggested we might use it against other people.

“Both Mrs. McSheffrey and I said the information is over 100 years old. What information could we possibly use against anyone?’ We explained that we simply wanted to determine who was buried there so we could start to do something about the graveyard.

“He became pretty hostile when we told him we wanted to do something about the graveyard. He said, ‘I don’t believe either one of you are qualified to do anything about the graveyard. I would bring someone up from Ottawa University who is much better educated that either of you and who is really qualified to do this kind of research.”

At this stage, Mrs. McSheffrey decided to abandon the project since the parish priest had expressed such displeasure and it was not clear whether he would even permit access to the church records.

Catholine was unwilling to concede defeat and said, “I decided that I was going to continue on with the work. I didn’t know how I was going to do it but I had made a promise and I intended to keep it.”

She called Father Cauley in Farrelton and explained the situation. He said he wasn’t surprised by this development but he said, “leave it with me, I’ll give him a call.”

Shortly afterwards, Catholine received a telephone call from Father O’Donnell who said, “when would you like to come down to look at the books?” She replied, “as soon as possible.”

Father O’Donnell was emphatic, “this is the way it’s going to be. I’m not going to be in my office while you go through the books. I’ll give you three days and that’s it.”

With great relief Catholine replied, “I’ll be there.” She called Mrs. McSheffrey to let her know about the latest development but she declined to participate any further.

It wasn’t long before Catholine realized that it would take much longer than three days to go through all the parish material, so once again she spoke to Father O’Donnell to explain her dilemma. She said, “I think I can complete my work if I can work all one night.”

After giving the matter some thought, he responded that he was going away overnight to Ottawa and she could have access all night-long on this one-time only basis.

Catholine began to work laboriously copying the information longhand as she had no access to a typewriter or photocopier machine. All night-long she wrote out the names of those who were buried in the old Martindale Parish cemetery and the dates of births of deaths.

During this night vigil, she made an intriguing discovery. It was an old diary kept by the first parish priest at Martindale and it was replete with information about early days in the area. Catholine said, “All the records were kept in the safe and I came across a diary there which had been kept by Father Blondin. It was a fascinating account of the early settlers in the parish.”

Father Blondin wrote about his experiences and challenges and it was evident that he really loved the people of the parish. He describes their living conditions as very poor and how they brought him food to help him when he first arrived. Soon the priest began to raise his own livestock so he wouldn’t be taking food off the tables of the parish.

“There was a lot of information recorded about the early settlers,” said Catholine, “but unfortunately, I had no way to copy the information in the diary.”

She realized that she would not have enough time to read the diary in full so she put everything back in the safe at the end of the night and left. When she knew Father O’Donnell was back, she called him once again to ask if she could have more time with the diary but he would go no further and the response was unequivocally, “no.”

The unfortunate part of this is that nobody knows what happened to that diary it was destroyed or lost along with all the other early records from the parish shortly afterwards. Catholine said, “I felt so sad about the loss of that diary because I felt it was very valuable. It was like a history of the whole area. There was information in there about my grandparents, along with information relating to so many other families in the community.”

Not only did the diary and all the early records disappear but shortly afterwards, so did the entire graveyard.

Catholine recalls the day that will remain forever etched in her memory. “I got a telephone call one morning about 7:30 AM from my husband who had passed by the graveyard on his way to work that morning. He said, ‘I think you should go down to the old graveyard, there’s a bulldozer in there.’

“I couldn’t believe it. I put my children in the car and raced down there to see for myself. There was a bulldozer in there, it was Pat Lacharity’s bulldozer and he had dug a trench and knocked all the headstones into this huge pit. They were all broken up in the hole. I remember standing there crying and thinking ‘this is the end, what will I do now?’

“I drove back up the hill to St. Martin’s Church to see if the priest was there but I was told Father O’Donnell had gone to Ottawa. I went back down the hill to the graveyard and I could see that several of the headstones had been swept to the side of the road.

“I didn’t speak to Pat Lacharity but I think he could see how extremely distressed I was and he had put these few aside, but the majority of the headstones were destroyed in the trench.”

For days afterwards, Catholine waited to speak to the priest to ask him why he would this, but he would not see her. Finally, on Sunday morning she was still unable to speak to him directly, but during Mass he spoke to the congregation to explain his actions. He said the reason he had destroyed the graveyard was because he had checked with Ottawa University and they told him that in order to begin any restoration work, it would need to be leveled since it was on a sloped incline.

Catholine said, “I was so infuriated with this explanation that I got right up in the middle of the Mass and walked out. I went around and waited in the rectory for him to leave the altar. I thought this is the worst thing I had ever heard. Leveling a graveyard in order to restore it. What kind of restoration is this? What did Ottawa University know about the people of this area?”

As soon as the priest left the altar, Catholine confronted him and said, “you know that graveyard belongs to the people and that’s their history. You can leave here tomorrow and it doesn’t matter to you. You can go to some other parish but that graveyard and those records belong to the people of this parish.”

Furiously, she continued, “You probably don’t realize the effort that went into putting up those headstones. It was a winter’s work in the bush and many people made tremendous sacrifices to put up those memorials.”

She said by this time the fire was flying out of Father O’Donnell’s eyes. He was not a man accustomed to being challenged and he did not want to hear another word from this woman who was causing him so much trouble. There would be no further discussion.

The community was embarrassed about this development and pressure was brought to bear upon Catholine to be quiet about the matter and put it behind her. Her mother and father, who were very well respected people in the community, prevailed upon her to let the issue go.

Catholine said, “I think people were beginning to realize that their history had been lost and it was embarrassing that nothing had ever been done about the graveyard. Unbeknownst to me, the one person I would have had in my corner was Martin Brown of Venosta, but at the time I didn’t know Martin and I felt that I didn’t have any allies, so I let the matter drop.”

But the matter was never forgotten in Catholine’s mind. It simmered there just beneath the surface for about 10 years until she received a fateful telephone call which brought it all back to the forefront once again.

It was now the mid-1970s and Catholine and her husband Tom had established the Molly McGuire’s Pub in Ottawa. As Ottawa’s first Irish pub, it was a wild place with live entertainment every night. There were line-ups to get in the door and eccentric characters around every post. It was a bohemian atmosphere with a swinging door of musicians and roadies coming and going day and night.

Every night Catholine arrived to work dressed in a long black shawl. She would stand at the door and extend warm greetings to patrons as they arrived in droves to take up their positions at long rows of tables. As the night progressed they would drink gallons of draft beer and work themselves into a collective frenzy, dancing on chairs and tables to the rousing Irish music. Later Catholine would direct the bouncers to throw out the stragglers so they could all show up again the next night.

It was Catholine who booked the bands. She had become a talent agent and recruited Irish entertainers to tour North America. She booked gigs from one town to the next and handled a whole array of immigrations and border issues.

Sometimes it required travel to far flung locations to deal with all kinds of problems related to getting musicians from one place to the next – sober and in one piece. Sometimes, it involved just listening to someone pour their heart out. Catholine heard and saw it all.

CATHOLINE BUTLER

Circa 1979

In the midst of this sea of madness, there was still one constant and that was the Gatineau Valley. At every opportunity, Catholine escaped up to the green rolling hills where her ancestors had found respite and she would reconnect with her roots and her family.

It was during one of these days at Molly McGuire’s Pub that Catholine received a telephone call from Martin Brown, an elderly farmer from Venosta, who wanted to talk to her about the graveyard at Martindale.

For years Martin had been muttering about how upset he was over the desecration of the Martindale graveyard. He had also been advised to forget about it – to move on. But Martin couldn’t forget about it and finally someone suggested he should speak to Elaine McCay who was now away in Ottawa.

Catholine agreed to meet him at her mother’s home in Martindale. She suggested they should meet during the week as weekends were generally a busy time at the Gannon homestead with family gatherings and people arriving to visit.

Martin agreed and said he would bring along Eddie McLaughlin who was also interested. Catholine said she thought this was just another wild goose chase because over the years many people had privately suggested how outraged they were about the graveyard, but nobody was ever prepared to take any action and nothing was ever done.

Despite this, Catholine decided to meet Martin and hear what he had to say. So up the Gatineau she went, accompanied by her oldest son Liam. She recalls that initial meeting as a very formal one, set in her mother’s dining room, with Martin Brown and Eddie McLaughlin on one side of the table and Catholine and Liam on the other side.

“I had often heard of Martin Brown,” she said, “but we had never met before this time.” He asked Catholine to speak to him about the graveyard, about what she had done and about her involvement with the graveyard.

She said, “I thought, I’m just going to let them have it, the way it is.” And she spoke to them about everything, about her thoughts, about what she had done in relation to the graveyard, and about her confrontations with Father O’Donnell. She spoke for a long time and then there was complete silence.

At the end of it, she said, “you know, this is a very Irish situation. From the time the Irish arrived here, they’ve had the short end of the stick, and this is the short end of the stick with this graveyard.”

There was total silence. Catholine said, “I waited for a few minutes and still nothing from across the table. The two of them just sat there looking at me and I thought, ‘well, I guess they’re mad’.” So she got up to leave the table and said, “well, I’ve said my peace, that’s all I have to say.”

Martin said, “Just a minute, where were you born?”

Catholine said, “I thought he was thinking, ‘where did this fanatical, off-the-wall lunatic come from?’ So I said, ‘I was born right here’ and I pointed to the sitting room behind me.

Martin said, “I can’t believe it.”

By this time, Catholine was feeling kind of embarrassed and wasn’t sure if he was so mad that he thought someone this radial and couldn’t have come from the Gatineau.

“He said, ‘I can’t believe it. I’ve been to Ireland many times and I would swear you were from Ireland. I can’t believe you were born in this house. How come I haven’t run into you around here before? How come I never heard about you until I started trying to find out about the graveyard?’”

“Well, you can check with my mother,” said Catholine, “she’s right here and she’ll confirm that I was born right in that room over there.”

Martin said “I’m just flabbergasted at the way you speak about this graveyard. You tell me what we have to do to get that graveyard put right and I’ll be right there with you.”

“I couldn’t believe what was happening that day,” said Catholine. “After all these years, someone was finally going to help me. I told him that I had all the names along with the dates and what we had to do was put up a stone with all the names on it.”

Since the early records had all disappeared from Martindale Parish, Catholine held the only record of all the names and dates of the people buried in the cemetery. The information was all hand-written and had been carefully guarded all these years. The monument would finally give recognition to those who found their final resting place in the soil at Martindale.

Martin said, “Anything else?”

“Well, a Celtic cross would be good,” ventured Catholine, “but we’re looking at thousands of dollars.”

Martin said, “Right now, concentrate on what needs to be done. You concentrate on what needs to be done for that graveyard and Eddie and I are going to work with you.”

The first thing was to determine how much it would cost to raise a monument and Martin asked Catholine to make some inquiries. She contacted Laurin Stonemasons who handled gravestones for much of the area and presented all the names and dates for a quotation.

They assessed the information and advised that it was a big job since one slab wouldn’t do it. It was going to require three separate stones engraved front and back.

At that time it was estimated that the monument would cost $2,300. This would include engraving the stones, transporting them from Ottawa to Martindale, and erecting the monument in the cemetery.

Catholine said, “I thought that was in insurmountable sum of money and I couldn’t imagine how we would raise these funds.” She spoke to Martin and he reassured her saying, “Don’t worry child, the money will come. Never forget, no matter what happens or where you go, the wee ones will always be with us to protect us.”

They talked it over and finally Catholine suggested, “Why don’t we run a dance at Farrelton Parish Hall. We could have a bar and that would help us to raise some money. We probably won’t make the money on the door but we’ll make it on the bar.” It was agreed. Catholine would arrange the entertainment and Martin would take care of the liquor license.

Catholine spoke to the Ottawa Gaels who had played at Molly McGuire’s. When she explained the nature of the booking the musicians headed by Don Cavanagh declined to accept any payment. They said the project was not just for the settlers at Martindale, it was a memorial for all Irish people and their descendants.

Catholine then received a telephone call from Martin who advised they had hit a snag with the liquor license. They needed a special permit license but when Martin spoke to the liquor control board, they advised that written consent from three hotels in the area was required in order to be grant a license.

Right away Martin spoke to three local hotels. The first two were run by French families and they had no problem whatsoever signing the consent. It was the third hotel where they ran into a problem.

The owner was of Irish descent and some of her ancestors were among those interred at Martindale cemetery. When approached by Martin, she said, “I can’t sign this. I’ve had a very bad year financially.” Martin reasoned, “but it’s only for one night.” She was adamant, “no I won’t sign the consent.”

When Catholine heard about the situation, she said, “that’s $1,000 out the window.” They realized that they would have to be totally reliant on the door and they really needed get the word out with posters and word of mouth. They put posters up everywhere and Martin got the word out and around the community. On the night of the event there was a full house and Catholine said, “I was even surprised at some of the people who turned up.”

In order to work around the liquor issue, they brought in bottles of whiskey from Molly McGuire’s and, under the table, Catholine would ask those who arrived up to purchase coffee, if they wanted a “little something special in that drink.”

As the band played and the room was in full swing, old farmers would stagger up to the food concession and say, “Elaine, pour me another shot of that coffee.” It was a great night and people left satisfied they had contributed to a good cause and everyone was very happy since they had lots of drinks and didn’t have to pay for them.

They grossed about $1,000 on the door, far short of their goal but at least it was a down payment on the monument. Catholine took the cash in to Laurent and explained they needed to figure out how to raise the rest of the money.

A FRONT VIEW OF THE MONUMENT with the names of all those buried in Martindale Pioneer Cemetery.

Shortly afterward, Martin called Catholine and said, “don’t worry about the money. It’s all taken care of, just go ahead and get the job started.” Catholine suspects that the balance of the funds came out of Martin’s pocket but there was nothing further said on the matter.

They agreed that the stone would be decorated with fleur-de-lys and shamrocks. Finally there it was, after all these years, a monument finally erected in memory of all those early settlers who were buried in Martindale pioneer cemetery.

By this time, Father Marois was the new parish priest at Martindale, and he indicated that he would like to see his name placed on the monument as part of the dedication ceremony. Although Father Marois had little or no involvement in the actual process, Catholine and Martin agreed that they had no objection to his name being inscribed on the stone.

Both Martin and Catholine declined to have their names engraved on the stone as they did not wish to detract from the names of those who were being commemorated by this memorial.

At the ceremony, the descendants of those who were buried in the cemetery were invited to come and read off the names of their ancestors. Catholine read the names Martin Gannon and Mary Egan, who were her great-grandparents who immigrated from Castlebar, County Mayo in Ireland.

A BACK VIEW OF THE MONUMENT with the names of all those buried in Martindale Pioneer Cemetery.

It was an emotional event to finally see the culmination of so many years’ work, but it was far from complete. There was still the dream of seeing a Celtic cross erected on the site but it was hard to imagine how this could be accomplished.

Once again, Martin contacted Catholine. He had a plan regarding the Celtic cross. He had been speaking to a number of people who preferred to remain anonymous but who wished to put forward the funding to assist with the erection of a cross.

He asked Catholine once again contact Laurin Stonemasons to determine the cost of a Celtic cross. They estimated the cost at $10,000 and Catholine reported the information back to Martin. He told her that she had a green light to proceed. The donors had expressed satisfaction with her work on the monument and now they wanted her to come up with a unique design for the cross.

Catholine contacted her friend Ethna O’Kane, who was living in Kingston, Ontario. Ethna, a Belfast-born artist, had studied Celtic art and design in Ireland. She understood clearly Catholine’s vision for the cross and set to work. In the wheel of the cross, a sailing vessel would represent the ordeal of crossing the Atlantic in coffin ships and the women with their children represented those who had died on the journey.

It was an enormous undertaking and Ethna had to lay paper out 10 feet long to prepare a scale drawing of the design. After working laboriously on the project, Ethna delivered a prototype to Catholine for approval. She took it up to Martin for his review and said, “Martin had tears in his eyes when he saw it. He said that was exactly what he wanted.”

Laurin examined the design and said this would be the biggest piece of work they had ever undertaken. It would have to be done in Granby, Quebec and it was going to take quite awhile to complete. Catholine said, “we’ve waited all these years to get to this stage, so it really isn’t going to make much difference as long as it gets done.”

Both Catholine and Martin felt the inscription to dedicate the monument should be in three languages: Irish, English and French. The words were provided by Professor Gordon McLelland, a visiting professor from Donegal who was teaching Celtic Studies at Ottawa University.

Over the years Catholine had become deeply immersed in Celtic culture and studied Irish folklore and language under the direction of Professor McLelland. A few years earlier she had also participated in a summer school held in the Gaeltacht area of Donegal to study the Irish language.

CATHOLINE in 1981 in her mother’s kitchen speaking with Conor O’Neill of Skyline Cable prior to leaving for Western Canada.

Professor McLelland provided the following inscription: “May the light of heaven shine on the souls of the Gaels who left Ireland in the years of the Great Famine to find eternal rest in this soil. They will be remembered as long as love and music last.”

In this period there was much turmoil in Catholine’s life and her marriage had sadly come to an end. There had been a bankruptcy and the family lost their business and their farm up the Gatineau. Her children were scattered and there was a great deal of anguish when Catholine moved out west to Alberta to re-establish her life.

But there was more to come. The greatest and most crushing blow occurred on October 19, 1981, when her oldest son Liam was tragically killed in a car accident outside Banff, Alberta. First her infant son and now her eldest son were buried at Martindale.

LIAM McCAY

1959-1981

LIAM’S MEMORIAL in the new graveyard.

Despite everything, Catholine and Martin remained in contact and firmly committed to finishing the project. Finally, Martin contacted Catholine with the news that the cross had been erected at Martindale cemetery and what a magnificent piece of work it was.

He said, “you must come back out to the Gatineau. We must have a dedication ceremony.” He impressed upon Catholine the need to document these events saying, “this is a very important piece of history and it wouldn’t surprise me if in years to come people will arrive here from far away to see this cross.”

There was some irony in the completion of cross. At the time, Catholine would not have had any financial means to travel given her diminished means. The only reason she was able to travel was because of Liam’s death. He had left behind an insurance policy which allowed Catholine to return for the dedication of the cross on September 19, 1982.

“When I arrived in Ottawa, a young fellow by the name of Gerrard McMullen offered to help in any way he could,” said Catholine. “Also, Max Keeping of CJOH TV, a very good friend, made a car available to me for transportation. This allowed me to get around to the newspapers, the radio and television stations, and to get the word out about what we were doing.”

CATHOLINE gives an interview to Conor O’Neill of Skyline TV at the memorial ceremony for the Celtic cross at Martindale Pioneer Cemetery.

Conor O’Neill, the Co-ordinator at Skyline Cable in Ottawa, was interested in covering the event and he arranged for a crew to travel up the old winding highway which followed the Gatineau River up to Low, Quebec.

Martin felt it was important to have a priest who could speak the Irish language to commemorate the event and asked Catholine if she might be able to arrange for this.

He arranged for a special cake to be baked to commemorate the pioneers.

She called her friend John Fitzgerald in New York City and explained what they needed. She said, “John already know the situation. He knew what I had been through and he knew all about the graveyard and the Celtic cross and he wanted to help. He was a writer for the Western People, a newspaper based in County Mayo and he had already written an article about this graveyard.”

When John informed Catholine that he had located an Irish priest from Connemara in the West of Ireland named Father O’Malley who was now located in Guelph, Ontario, she was delighted. Since she now had some funds available, she offered to pay for Father O’Malley’s travel costs to Ottawa and arranged to pick him up at the airport.

Catholine said, “I was astounded when I learned his name was O’Malley. In the new graveyard at Martindale there are a number of O’Malley’s buried there. They have a huge cross overlooking their burial site on which they had obviously spent a considerable amount of money. These people were originally from County Mayo.

“When I spoke to Father O’Malley, he told me that his father was from Westport, County Mayo. I was kind of blown away that he was answering this call as most of the people who were buried in the pioneer cemetery were originally from around the Westport area and County Mayo.

“Another strange coincidence that really left kind of amazed me was that the O’Malley family had originally donated the land on which the pioneer graveyard is located.”

The O’Malley Connection : From County Mayo to the Green Hills of the Gatineau

By FATHER TOM O’MALLEY

St. Michael’s College, Dublin

MARTIN BROWN dressed in his Sunday best stands for a photo as Catholine speaks to Skyline TV at the memorial ceremony for the Celtic cross at Martindale Pioneer Cemetery.

A magnificent limestone Celtic Cross stands in Pioneer Cemetery, overlooking the rolling countryside of Martindale village, 56 kilometres north of Ottawa in Gatineau County, Quebec.

THE MEMORIAL CEREMONY at Martindale Pioneer Cemetery.

It is inscribed in Irish, English and French with these words: “May the light of heaven shine on the souls of the Gaels who left Ireland in the years of the Great Famine to find eternal rest in this soil. They will be remembered as long as love and music last.”

AT THE CEREMONY to bless the Celtic cross overlooking the cemetery.

The inscription memorializes the Irish who came to Martindale in the 1847-50 Famine era, surviving the rigours of their ocean voyage, sickness and the many burdens and difficulties associated with establishing a new life in a strange country.

AFTER THE MEMORIAL for the Celtic cross a celebration was held at Martin Brown’s farm. He arranged for a special cake to be baked to commemorate the pioneers.

At Pioneer Cemetery (so named as it was the first buying ground for that era), a triple cenotaph on which 72 names and dates of death of the original immigrants are fully recorded now stands to their memory.

On September 18, 1982, I blessed that Celtic Cross and this came about as follows. The organizer of this event, Elaine McCay [Catholine Butler], phoned her friend John Fitzgerald in New York asking him to find an Irish speaking priest for the blessing, as this would be appropriate for the pioneers who spoke Irish.

John contacted Father Sean Hourigan, a Holy Ghost priest of my ordination year, who informed him that I was a fluent Irish speaker already in Canada. In 1981, I had arrived in Canada and was now associated pastor in the parish of Guelph, Ontario. Needless to day, I was contacted immediately.

I agreed to go and this was followed by a frantic search for the mass text. It arrived from New York two hours before I flew out from Toronto en route to Ottawa.

In Ottawa, I was met by Elaine. She is of Castlebar lineage and her ancestors, the Gannons, had settled in the Gatineau Valley. She is a vibrant woman, student of the Gaelic language and culture at Ottawa University and the chief promoter and fund canvasser for the erection of the memorial Cross.

She was delighted to learn that I was from the West of Ireland and of the name O’Malley because the land for Pioneer Cemetery was given by the O’Malley family. Most of the pioneers came from County Mayo and County Galway.

Soon we got underway, speeding north for 57 kilometres through the beautiful Gatineau hills, tinted golden by the onset of the fall. Darkness came down but sufficient light lingered to see the mountains loom up on either side of our ribbon-like twisting road. Up hill and down dale we plunged, coasting along the Gatineau River, a slate of silver in the gathering dusk.

Along this river came the pioneers of old, from distant Quebec City over 450 miles away, portaging their canoes over wild stretches of country. They had availed themselves of government grants to reclaim land through clearance and drainage and make farms. Most of the Irish opted to pioneer the Gatineau valley.

Our first stop was the home of Gladys Gannon, Elaine’s mother, a gentle, refined woman, fussing in Irish fashion over her daughter as if she was still a teenager. She is a sturdy woman, of sturdy stock. She is well read, a teacher, a farmer’s wife, and a repository of wisdom born of experience.

Her log house was snug and unpretentious. She sat me in unusual rocking chair – all moving wooden parts with an adjustable footstool. Promptly, she thrust a drop of the “craythur” into my hand, no protestations accepted. I was home!

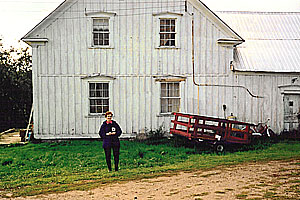

CATHOLINE stands outside Martin Brown’s family homestead in Venosta, Quebec.

It was late when Elaine and I set off in the darkness to meet my host for the night, Martin Patrick Brown, who has roots in Ballina, County Mayo. We sped off over dirt brown roads, not signposted until at last, we turned into a long unlit winding lane which led us to a large white log house, Martin’s ancient family home. A few yards away was a modern small bungalow. Here I was to stay. First to greet us was the friendly collie dog Monday.

Next appeared my host Martin, tall, lean, with a thousand welcomes sparking from his eyes. His youthfulness belied his 72 years. His handshake was firm, sincere. I felt at home. I was made at home.

His house bore the marks of contented bachelorhood. Out came the welcoming bottle. It had the makings of a long night! Conversation rolled on through the night, anecdotal humorous, new Ireland was meeting old Ireland, hands across the sea.

The next day was a beautiful day in this beautiful setting. I was in a green oasis valley, surrounded on all sides by tree-lined mountains. Martin explained that we were on the edge of the great Canadian wilderness that stretches north to the arctic circle.

I asked him, “how do we get out of here?” for I could see no obvious exit. My question brought gales of laughter from him. I had hit the nail on the head – the wilderness is beautiful but it can be a claustrophobic prison.

At noon, it was time to be on our way to Martindale for the memorial Mass in the little church of St. Martin. In the first years of the pioneers, residents of Martindale had to walk 12 miles to Farrellton for Mass.

Today, their descendants gathered to hear Mass said in Irish, the language of their forefathers. Only a few could understand. Present was Professor McLelland of Celtic Studies at Ottawa University, a Scot formerly of Dublin.

My co-celebrant of the Mass was another Holy Ghost Father and Parish Priest, Father Leo Le Blanc. After Mass, a happy-go-lucky jumble of people proceeded in glorious sunshine to the nearby cemetery for the blessing of the Celtic Cross.

The professor opened the proceedings with a brief history of the early pioneers. He was followed by the designer of the Cross, Ethna O’Kane from Belfast, who explained the symbols of the Cross.

The Celtic design on the Cross includes a ship and a man and woman holding a child. This ship depicts the Famine ships and the family unit is symbolic of the number of family members that died on the 450-mike trek from Quebec City to Martindale. I then blessed the Cross, taking my theme from the Book of Job 19:23:26.

“Wold that these words of mine were written down, inscribed on some monument with iron chisel and engraving tool, cut into the rock forever. This I know that my Redeemer lives, and he that last will take his stand on earth. After my awakening, he will set me close to him, and from my flesh I shall look on God.”

I likened the pioneers to Job, who, bereft of all worldly goods, with rock-like faith, placed unwavering hope that God would see them through to the end. On that day, we “with iron chisel and engraving tool” carved on that Cross a poignant reminder.

TWO DANCERS, JANET EGAN of Martindale along with a traditional Irish dancer took the offering up to the altar during the mass to bless the new cross.

The ceremony concluded with an exhibition of Irish dancing and fiddle playing. We all then retired to Martin’s for food and drinks.

Next day dawned glorious, so I postponed my trip back to Guelph to Wednesday. My day began with a visit to Martin’s ancestral log cabin. It was quite big, with ample loft space to accommodate a large family. Two things struck me as I entered the centre of the room.

The sheet-iron stove pipe after mounting a few feet was carried through the house before exiting, thus spreading heat round. In a corner stood a three to four foot-high pump shaft which supplied water, thus ensuring no freeze up in the harsh winters.

Along one wall lay a huge old fashioned dresser, still carrying the delph ware. A steep ladder in a corner led to the loft where the boys slept in summer time. In winter, they moved down to the warmth of the kitchen.

For the pioneers, the first snows of October were a warning to get down to the task of laying in the winter’s store of wood. Beyond the field lay the forest where there was an abundant supply of dead trees – cypress, spruce, and birch. These were loaded onto a big wood sleigh, hauled to the house to be cut into logs and corded in the shed for the winter.

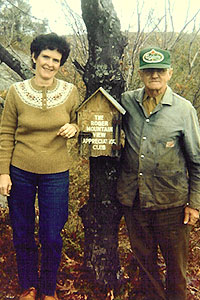

ETHNA O’KANE the Belfast-born designer of the Celtic cross at Martin Brown’s home following the dedication ceremony at Martindale Pioneer Cemetery.

Fire was constantly tended during the long winter. Cypress was best for the morning start, spruce throughout the day, and in the evening, birch.

Elaine told me, “my father told us that his father had often told him that the Irish in the Gatineau Valley participated in building bees. Neighbours gathered to build houses and barns and help each other to clear the land and sow crops.” In Ireland we called such a gathering a “meitheal” in Gaelic. It happened, I recall, at home when neighbours helped in ricking in the hay or thrashing the corn. Alas, this is now history.

Elaine joined us as we set off through the forest, on a long climb to the mountain top, a favourite haunt for Martin, a haven of solitude and peace. On our way up, following a path blazoned by axe cuts on trees, Martin drew my attention to a small clearing with a deep depression.

“There,” he said, “was Paudeen Murphy’s house. He was the soothsayer and his farm was here.”

“But,” I said, “I can see only trees.”

“Trees soon grow like grass here unless you keep them at bay,” replied Martin. Paudeen is long dead.

CATHOLINE and Martin Brown on the mountain top overlooking Rogers Lake on the Brown family farm.

Finally, we crested the mountain and there beneath us was a wonderful view over Roger’s Lake. For two hours, we sat in the clearing absorbing the fabulous scenery spread out before us, allowing the silence and solitude to seep into our tired limbs. We spoke quietly to each other, half afraid to dispel the magic by too loud a tone.

On a tree was a box. Here Martin had placed a visitor’s book. I signed it and am told it is still there.

Reluctantly, we made our way home in the fading light. Autumnal tints were heralding the approach of the glorious fall. The sky had taken on softer hues above the forest’s dark edge.

On our way down, Martin stopped at a small unnamed lake. Turning to me suddenly, he said, “In your honour and in gratitude for coming to us, I name this lake O’Malley Lake. I have a cartographer friend who will insert it on the map.” And he did.

The following day, Martin took me to see logging being done on his land. Three lumberjacks were busy logging a half acre of trees in no time. One logger axed a tree. Another on a monster machine, with each huge wheel controlled independently, hitched onto a tree and crawled down the mountain like a giant crab, overcoming all obstacles on route. The third logger cut into logs with a powerful saw there and then.

FATHER O’MALLEY at the top of the mountain overlooking Rogers Lake on Martin Brown’s farm.

This scene gave Martin the chance to tell me about logging in the old days. From October to April was the lumbering season. Then, the most able-bodied men headed for the forest to make that extra cash so badly needed. They lodged in makeshift houses called shanties. All through the winter, the axes never ceased falling, while horses pulled the logs down the river.

Piled high there, they awaited the spring thaw. It was then the river drivers came into their own as they guided the logs down the river. Very dangerous work requiring great skill and nimbleness as they made their way across the floating timber, breaking jams with axe and pike-poles. It was a rough, harsh life.

AT THE TOP OF THE MOUNTAIN is a box in which Father O’Malley left a not of appreciation.

That afternoon, we visited Venosta, a small village in the same parish as Martindale and met some friends of Martin. That night we dined again at Elain’s mother’s The next day, Elaine collected me at Martin’s for the trip home.

It was a sad parting from Martin. In Ottawa, we called to the TV studio to see the documentary on the blessing of the Celtic Cross. It was shown on TV in Ottawa and New York. I received a copy as a present. Another sad goodbye and I was airborne for Toronto. An unforgettable episode had ended.

POSTSCRIPT

In March 1984, I returned to Ireland as Bursar at St. Michael’s College. On March 8, 1985, Martin Patrick Brown, died aged 74 years. His last letter to me:

Hello Father O’Malley:

You may well think I have long departed from this planet considering I am six months or more behind in replying to your very welcome letters and cards. 1983 was not such a good year, at least for me, and a person does get down betimes. Had even hoped to get this to you before Paddy’s Day but not likely now.

Had a visit from Elaine a few weeks ago and she looks very well. The world seems to be going very well for her now. She also said you might be posted to Blackrock in Dublin this year. So I hope you make it back to the Gatineau before leaving Canada. My old shack is, if anything, more dusty now than when you were here in 1982. But, dusty and all, you will always be welcome here for as long as you wish to stay.

We still have solid winter here with 30 below in the mornings but a few weeks more it is sure to be milder and O’Malley Lake will be open again. Passed that way early winter and everything was silent as a grave.

Hope to hear from you soon.

Sincerely yours,

Martin Brown

[How happy are the wild birds, they can go where they will, now to the sea, now to the mountain, and come home without rebuke. – Welsh Seventeenth Century]

*

This article was originally published in the May 1994 edition of The Celtic Connection newspaper based in Vancouver, British Columbia.